Part VI: William Tyndale – The Father of the English Bible

The Changing Landscape of Early Modern Europe

By the early sixteenth century, more than a century had passed since John Wycliffe’s English translation of the Bible. In that time, England had emerged from civil unrest and was experiencing renewed political stability under the Tudor monarchy. The reign of Henry VIII marked the rise of England as a European power, and across the continent, new intellectual and religious movements were taking shape.

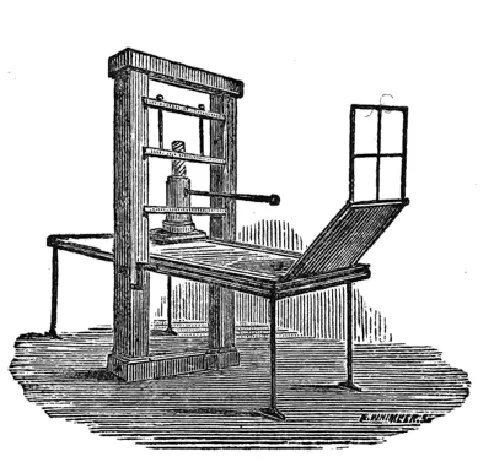

Print, Trade, and the Recovery of Ancient Texts

The invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century transformed the spread of knowledge. With movable type, biblical texts could be reproduced rapidly and at lower cost. Meanwhile, the rise of a literate middle class increased demand for books in the vernacular.

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 also had a lasting impact. Greek scholars fleeing westward brought ancient manuscripts long forgotten in the Latin West. These texts fueled a renewed interest in classical languages and directly contributed to Erasmus's production of the first printed Greek New Testament in 1516—a foundational text for future translators.

Reformation Thought in Continental Europe

In 1517, Martin Luther launched what would become the Protestant Reformation. His Ninety-Five Theses, posted in Wittenberg, criticized ecclesiastical abuses such as the sale of indulgences and called for a return to scriptural authority. Luther’s insistence on salvation by faith alone, apart from works, challenged centuries of Church teaching.

Among his most influential achievements was his translation of the Bible into vernacular German. Drawing from Hebrew and Greek sources, he prioritized the language of ordinary people. His goal was not just access, but clarity—a principle that would resonate deeply with other reformers, including William Tyndale.

Tyndale’s Early Life and Education

William Tyndale was born in Gloucestershire in the early 1490s. He studied at Oxford and Cambridge, where he encountered both the humanist scholarship of Erasmus and the growing calls for church reform. Gifted in languages—reportedly fluent in seven—Tyndale was exceptionally prepared for the work of translation.

While serving as a tutor, he was increasingly disturbed by the Church’s distortion of biblical teaching. When a clergyman claimed that it was better to be without God’s law than the Pope’s, Tyndale famously replied, “I defy the Pope and all his laws. If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest.”

Translation and Exile

In 1524, Tyndale sought official approval to translate the Bible into English. His request was denied. An earlier law from 1408 had outlawed unauthorized translations, and no English bishop was willing to defy it. Realizing that England offered no safety for his work, Tyndale left the country, never to return.

He settled in Germany, where he began translating the New Testament directly from the Greek. Though he met Luther, the two differed on several theological points and worked independently. Tyndale completed the New Testament in 1525, and soon copies were being smuggled into England—hidden in cargo and transported through sympathetic trading networks.

Reception in England and Court Intrigue

The reaction in England was immediate. For the first time, ordinary people could read the New Testament in their own language. The Church hierarchy responded with alarm, recognizing the threat to their authority. Yet the appeal of Scripture in the vernacular proved unstoppable.

Tyndale’s writings also found their way into royal hands. Anne Boleyn, future queen and wife to Henry VIII, possessed copies of both The Obedience of a Christian Man and the 1534 New Testament. Although the king publicly opposed reform, he later appropriated its language and ideas for political ends—chiefly in severing ties with Rome. Tyndale, however, remained a target of the crown.

Continued Work and Final Betrayal

Despite the constant threat of arrest, Tyndale continued refining his New Testament and translating the Old. He completed the Pentateuch in 1530 and Jonah in 1531—all while evading spies and informants. His 1534 New Testament, the product of years of revision, is widely considered his most accurate and poetic edition.

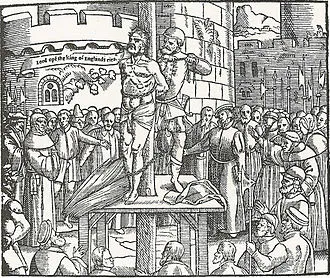

In 1535, he was betrayed by a supposed ally, arrested in Antwerp, and imprisoned in Vilvoorde Castle. After eighteen months, Tyndale was condemned as a heretic. On October 6, 1536, he was executed—strangled, then burned at the stake. His final words were a prayer: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

Posthumous Influence and Recognition

Within a year, Tyndale’s prayer was answered. In 1537, Henry VIII authorized the printing and distribution of the Coverdale Bible, much of it based on Tyndale’s own work. Ironically, the monarch who condemned him now sanctioned a Bible that relied heavily on his translation.

Tyndale’s influence on the English language and biblical tradition is profound. An estimated 80–90% of the King James Version reflects his wording. Even modern translations, such as the Revised Standard Version of 1952, retain much of his language. His legacy endures not only in words, but in the very principle of Scripture made accessible to all.

A Legacy of Faith and Language

William Tyndale combined scholarly excellence with deep personal conviction. He worked alone, in exile, under constant threat, and ultimately gave his life for the cause of Scripture in the common tongue. His work laid the foundation for all English Bibles that followed. He is rightly remembered as the Father of the English Bible—a title earned not only by his pioneering translations but by his unwavering commitment to truth, clarity, and the transformative power of God’s Word.