Part VII: The Reformation Bibles — Scripture in the Vernacular

Shaping of English Christianity

The Protestant Reformation was not merely a theological movement; it was also a revolution of literacy, language, and access. Central to this transformation was the translation of the Bible into vernacular tongues, especially English. For centuries, Scripture had remained inaccessible to the average believer, guarded behind the walls of ecclesiastical Latin and subject to the interpretive authority of the clergy. But by the 16th century, as reformers challenged the authority of the Church and emphasized the priesthood of all believers, access to God’s Word in one’s own language became a defining mark of Protestant identity.

The Coverdale Bible (1535): The First Complete English Bible in Print

Myles Coverdale, a contemporary and admirer of William Tyndale, holds the distinction of producing the first complete printed English Bible in 1535. This achievement came at a time of great peril. Just one year later, Tyndale would be executed for heresy—his crime being the translation of the New Testament into English without ecclesiastical permission.

Although Coverdale lacked Tyndale’s scholarly command of Hebrew and Greek, he was a skilled editor and compiler. Relying heavily on Tyndale’s translations of the New Testament and parts of the Old Testament, Coverdale supplemented the rest with material drawn from the Latin Vulgate and German translations, likely influenced by Martin Luther. Commissioned under the patronage of Thomas Cromwell, Secretary to King Henry VIII, Coverdale’s translation marked a turning point: it was the first full English Bible made publicly available in print, bringing the Scriptures into the hands and homes of ordinary English speakers.

The Matthew Bible (1537): A Fusion of Reformers’ Work, Approved by the King

Following Tyndale’s martyrdom, his friend and protégé John Rogers assumed the task of continuing his translation legacy. Compiling Tyndale’s New Testament and completing portions of the Old Testament, Rogers translated the remainder through a blend of existing translations and original work, up to 2 Chronicles. To avoid suspicion due to Tyndale’s association with heresy, Rogers published the Bible under the pseudonym "Thomas Matthew"—hence, the Matthew Bible.

Despite the risk, the Matthew Bible received surprising favor. When a copy was passed from Archbishop Cranmer to Thomas Cromwell, it ultimately reached King Henry VIII. Perhaps unaware of its Tyndale origins—though Rogers subtly included the initials "W.T.." at the end of the Old Testament—the king approved it, and it bore the phrase, “Printed with the King’s most gracious license.” With this endorsement, the English Bible was, for the first time, legally printed and distributed with royal sanction, a monumental shift in English religious life.

The Great Bible (1539): The Authorized Church Bible

Although the Matthew Bible was legally approved, its marginal notes were controversial and its links to Tyndale problematic. Cromwell, seeking a more neutral and official translation, turned once again to Coverdale. In 1539, Coverdale produced a revised edition—known as the Great Bible—printed in Paris with the permission of the French king and brought to England shortly thereafter.

Its name derives from its size (pages measuring roughly 9 by 15 inches), making it ideal for public reading in churches. The Great Bible was so valuable that it was often chained to church pulpits to prevent theft, earning it the moniker “Chained Bible.” By royal command, every parish in England was to acquire a copy, solidifying the Bible’s presence in communal worship and making it the first “authorized version” of Scripture in English. Ironically, Henry VIII, who had once condemned Tyndale, now mandated the reading of a Bible that heavily relied on Tyndale’s foundational work.

The Geneva Bible (1560): The People’s Bible

The tide turned once again under Queen Mary I, known as “Bloody Mary,” whose brief reign (1553–1558) marked a brutal return to Catholicism. Over 300 Protestant reformers were martyred, including John Rogers, the compiler of the Matthew Bible. Many others fled into exile, seeking refuge in Protestant strongholds like Geneva, Switzerland.

It was there, under the leadership of figures like John Calvin, William Whittingham, and Miles Coverdale, that English exiles undertook a fresh translation: the Geneva Bible. Published in 1560, it was both scholarly and accessible, incorporating chapter and verse divisions for easier reading and study. Its marginal notes, deeply Calvinist and anti-papal in tone, made it wildly popular among Puritans and laypeople alike.

This Bible became the favored version of English-speaking Protestants for decades, known affectionately as the “Breeches Bible” for its rendering of Genesis 3:7. It was the Bible of Shakespeare, John Bunyan, and the Pilgrims. It was the Geneva Bible—not the King James Version—that arrived with the Mayflower and shaped the religious ethos of early American settlers.

The Bishop’s Bible (1568): A Response to Geneva

Though the Geneva Bible enjoyed widespread popularity, it lacked official ecclesiastical sanction. To counter its influence, Archbishop Matthew Parker initiated a new translation under the oversight of the Church of England. The result was the Bishop’s Bible, published in 1568. It followed the Great Bible’s textual base but toned down the radical annotations found in the Geneva edition.

Although grand in design and rich in woodcut illustrations, the Bishop’s Bible was less successful as a literary or scholarly work. It was primarily intended for liturgical use and was never widely embraced by the general public. Even Queen Elizabeth I, whose image adorned the title page, never formally endorsed it. Nevertheless, it became the standard pulpit Bible and served as the official translation until the publication of the King James Bible in 1611.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Image

|

Image

|

|

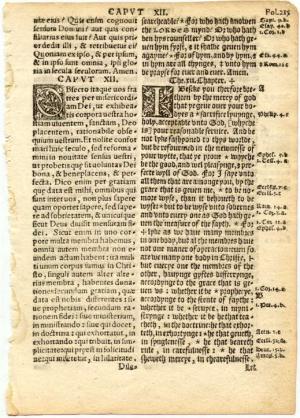

Page from a Coverdale Bible, 1538 |

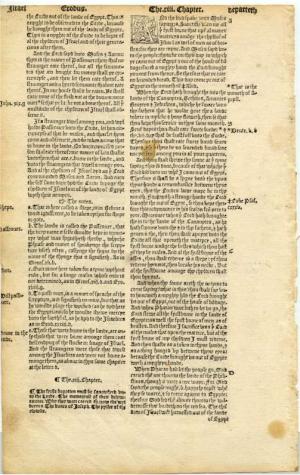

Page from a Matthews Bible, 1539 |

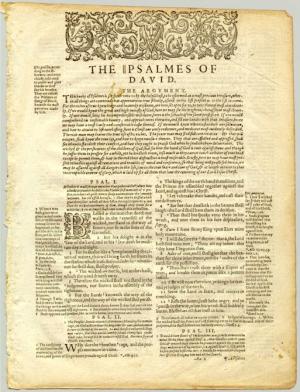

Page from a Great Bible, 1541 |

Page from a Geneva Bible, 1609 |

A Legacy of Risk, Reform, and Revelation

The Reformation Bibles—Coverdale, Matthew, Great, Geneva, and Bishop’s—represent more than historical artifacts; they are testimonies to the enduring desire for divine truth to be known and shared. These translations were produced under threat of imprisonment, exile, or death, yet their influence endures. They shaped not only English religious identity but also the broader contours of Western thought, democracy, and human rights.

Each translation contributed in some way to the monumental King James Bible, which was published in 1611 and synthesized the legacy of its predecessors. But it was these earlier works—sometimes smuggled across borders, hidden in homes, or read by candlelight—that laid the groundwork for one of the most profound revolutions in history: the unleashing of God’s Word into the language of the people.