Part V: John Wycliffe

A World Without the Word

The name John Wycliffe (c. 1328–1384) resonates in the annals of church history as a prophetic voice in a time of deep spiritual obscurity. Often hailed as the “Morning Star of the Reformation,” Wycliffe stood at the dawn of a transformative era, boldly challenging institutionalized corruption and striving to return the Christian faith to its biblical foundations. His life's work laid critical groundwork for the Reformation that would erupt a century later. To appreciate his impact, one must first understand the religious, political, and linguistic landscape of medieval Europe—a world where access to Scripture was tightly controlled and shrouded in scholarly exclusivity.

From Constantine to the Medieval Church: The Rise of Ecclesiastical Power

Following the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century and the subsequent Edict of Milan (313 CE), Christianity shifted from a persecuted sect to the official religion of the Roman Empire. While this marked a triumph for religious freedom, it also laid the foundation for an increasingly politicized Church. Over the ensuing centuries, the Christian Church—now unified under Roman Catholicism—grew into a powerful institution, blending spiritual authority with temporal governance.

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Church had evolved into a vast hierarchy, with the papacy asserting supreme power over both religious and political life. Though this period saw genuine acts of piety, monastic reform, and cultural flourishing through institutions like universities and cathedral schools, it also became increasingly marked by clerical abuses, doctrinal distortions, and spiritual decay.

The Withholding of the Word: Linguistic Barriers and Ecclesiastical Control

Perhaps the most devastating consequence of the Church's centralization of power was its monopolization of Scripture. In the early centuries of Christianity, the New Testament had been written in Koine Greek, the vernacular of the Eastern Mediterranean, allowing for broad accessibility. Even the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek (the Septuagint), a clear indication of the early Church’s missionary concern for making God's Word available in common language.

However, as the Western Roman Empire crumbled and Latin supplanted Greek in ecclesiastical and legal life, the Scriptures became increasingly removed from the everyday language of the people. The Latin Vulgate, translated by Jerome in the late fourth century, became the authoritative version of the Bible in the Western Church. Over time, Latin ceased to be a living, spoken language for most Europeans, yet the Church retained it as the exclusive language of Scripture and liturgy.

While this may have initially stemmed from a desire to preserve doctrinal accuracy, the practical result was that Scripture became inaccessible to the vast majority of believers. Only the highly educated clergy—often trained in cathedral schools or monastic centers—could read and interpret the sacred text. For the average layperson, the Word of God was mediated exclusively through priests, many of whom distorted it to serve political, economic, or personal ends.

Theological Corruption and Ecclesial Abuse

By the 13th and 14th centuries, critiques of Church corruption had grown increasingly urgent. Doctrines such as transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ), the sale of indulgences, and papal infallibility were taught as unquestionable truths. The Church's claim to act as the sole interpreter of Scripture granted it immense control over the spiritual lives—and material wealth—of the faithful.

One of the most egregious abuses was the practice of selling indulgences, which promised temporal or eternal relief from sin’s penalties in exchange for financial payment. This effectively turned salvation into a commercial enterprise. Additionally, the Crusades, originally framed as holy wars, devolved into violent campaigns that included massacres of Muslims, Jews, and even fellow Christians—all ostensibly justified in the name of Christ. In such an environment, devoid of widespread scriptural literacy, the people had no reliable means to verify whether the Church’s teachings aligned with biblical truth.

Wycliffe’s Vision: Scripture in the Vernacular

Into this darkness stepped John Wycliffe, a scholar and theologian from Oxford. Deeply disturbed by the corruption within the Church and the clerical abuse of power, Wycliffe began to call for a return to Scripture as the sole authority for Christian life and doctrine (sola scriptura). He argued that every believer should have access to the Bible in their own language—a revolutionary and dangerous idea in the 14th century.

Wycliffe’s most enduring contribution was the translation of the Latin Vulgate into Middle English, a monumental task he undertook with the help of his followers, known as the Lollards. Though technically illegal—since Church authorities forbade the translation of Scripture into vernacular languages without approval—Wycliffe’s Bible circulated widely, empowering laypeople to read and interpret God’s Word for themselves.

For Wycliffe, translation was not merely a linguistic project but a theological imperative. He believed that Scripture, not the Pope or Church tradition, was the ultimate authority. His writings challenged the papacy, criticized the wealth and power of the clergy, and emphasized salvation by faith rather than by works—a theme that would later echo throughout the Reformation.

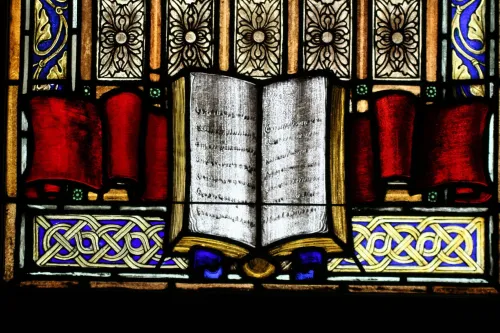

Stained Glass Window Representing Sola Scriptura

Legacy and Impact

Though Wycliffe died in 1384, his influence only grew after his death. In 1415, the Council of Constance condemned him as a heretic, and in 1428, his remains were exhumed, burned, and scattered. Yet his ideas lived on. Jan Hus in Bohemia adopted many of Wycliffe’s teachings, and a century later, Reformers such as Martin Luther would echo his call for vernacular Scripture and ecclesial reform.

Wycliffe’s commitment to biblical accessibility paved the way for the Protestant Reformation and the modern concept of religious liberty. His English Bible, though based on the Latin Vulgate rather than original Hebrew and Greek texts, marked the beginning of a movement that would culminate in the translation of the Scriptures into dozens of languages and dialects. In the English-speaking world, Wycliffe stands as a foundational figure—an early voice in the long struggle to return God's Word to the people.

The Reformer Before the Reformation

John Wycliffe’s life and ministry stand as a beacon of courage and conviction in an age of institutional darkness. His bold insistence on the authority and accessibility of Scripture was a direct challenge to the theological and political structures of his day. Though he lived more than a century before Luther, his work helped prepare the ground for the Reformation. In reclaiming the Bible for the common person, Wycliffe restored light to a world that had too long been cloaked in spiritual ignorance. His legacy is not only one of reform but of restoration—returning the Church to its foundation in the living Word of God.